Introduction

In the article titled Disciplinary charge formulation, I touched briefly on interviewing witnesses as part of the investigation of an alleged offence. Dealing with witnesses is however a critical aspect of the deployment of evidence in a disciplinary hearing and needs special attention.

This article looks specifically at utilising the testimony of witnesses as a means to place relevant evidence before the person presiding in the case, tasked with deciding on guilt/innocence and the appropriate sanction, in case of a guilty finding.

Testimony of witnesses within context

The point of departure and assumption is that, at the commencement of the case, the person presiding in a disciplinary case (hereinafter “decision maker”) is unbiased, has no prior knowledge of the matter at hand (which could affect his/her objectivity) and is approaching the matter with an open mind.

The first piece of relevant information, which is placed before the decision maker, is the charge, which, until proven on at least a balance of probability, has the status of an allegation. It is also noteworthy to emphasise that a particular premise in our law dictates that the accused employee is regarded innocent until proven guilty.

It is also important that the charge, as formulated and presented, provides the parameters within which the decision maker has to make his/her findings regarding guilt and sanction. He or she cannot, once he/she has come to know what transpired in the matter, deviate from the charge, as formulated. For instance, if it is established on the strength of the tested evidence, that the employee committed an offence other than the offence he/she is charged with, a verdict of “not guilty, as charged” has to be pronounced. Cross reference in this regard the articles: Disciplinary charge formulation and A second bite at the proverbial cherry.

The decision maker therefore has to be convinced, at least on a balance of probability, of the guilt of the employee in respect of the charge, on the strength of relevant information adduced as evidence during the disciplinary proceedings.

Evidence can take various forms, such as documentary evidence, real evidence (objects or exhibits), arguing circumstantial evidence, evidence adduced by the re-enactment of events and/or inspections in loco and last, but not least, the testimony of witnesses.

Any person fighting a case in court or in a tribunal, will tell you that first preference is to be able to prove your case without calling any witnesses, if at all possible, because in many instances, a witness is a potential “hole” or “weak spot” in one’s case, simply because, despite proper preparation of a witness, one simply does not have absolute control over this source of evidence. The witness has to go through a stringent scrutiny exercise and has to do so on his/her own, for the most part, with only limited assistance and some extent of “damage control” that could be exercised by the person calling the witness.

Questioning stages

For the proper deployment of evidence to happen, a witness is put through three modes of questioning, each with its own characteristics and requirements. Putting a witness through these 3 questioning stages, serves the purpose of testing the credibility and reliability of the witness’ testimony, while at the same time building in an element of objectivity.

These stages follow in chronological order. While all three stages are enablers, assisting the applicant (the employer in a disciplinary case, who is initiating the case) and the respondent (the employee in a disciplinary case defending him/her against the charge) with stating their respective cases on a need to basis. There is no obligation on the applicant or respondent party to testify or to call witnesses in substantiation of his/her case – these cases can be substantiated by other forms of evidence, not requiring viva voce (live, in person) evidence. By the same token, cross examining and re-examining a witness are optional opportunities, even when the witness is called to testify (more in this regard later in the article).

In consequence of the legal principle: whoever alleges must prove, the applicant party (the employer charging the employee in a disciplinary case) however has to substantiate his/her case by the submission of relevant evidence (otherwise there will obviously be no case) , which substantiation often consists of the calling of witnesses, but, theoretically, the calling of witnesses need not form part of the framework of evidence.

As we are focusing in this article on the calling of witnesses as a means of deploying evidence, a witness is put through the following 3 stages of questioning:

Examination in chief

This mode of questioning is applicable when either of the parties to the disciplinary proceedings questions its own witness whom he/she prepared for his/her testimony beforehand.

In the article titled Disciplinary charge formulation , I recommended that when investigating a case and interviewing potential witnesses, a potential witness should be requested to write down al he/she knows about the matter in question and then sign and date this statement. The party bringing the case and who intends calling the witness will then go through the statement with the witness, highlighting those pieces of information contained in the statement that would be helpful, relevant and even crucial to the substantiation of the case.

Once the essential elements of the witness’ statement are identified, the person calling the witness ideally should devise a questionnaire comprising of a range of questions to be put to the witness during examination in chief, designed to extract those factual evidence from the witness during the latter’s testimony. Any hearsay evidence, speculation or other forms of inadmissible evidence will be excluded from the questionnaire.

This questionnaire is then rehearsed with the witness, agreeing on the best way to answer these questions as concise, truthful and to the point as possible, drawing from the first-hand knowledge the witness has on the subject matter concerned. This then completes the preparation of the witness for examination in chief.

During examination in chief, the person calling the witness and putting questions to his/her witness, is prohibited from asking leading questions, that is, suggesting the answer to the question in the way the question is phrased. A simple example of a leading question is: “Do you agree that the incident happened on Wednesday?”. Rather, the question should have been phrased as follows: “On which day did the incident occur?”.

Although not strictly speaking prohibited, the questioner should refrain from persistently using so-called “closed questions” requiring a “yes “ or “no” answer, since such line of questioning can be objected to for the reason that it is open to manipulation. Nothing prevents the questioner and the witness to agree on some form of signal given by the questioner as a hint to the witness as to what to answer, however, that would amount to manipulation.

Obviously, such manipulation is less likely where the witness was properly prepared for testimony and knew beforehand what answers to give to the questions put to him/her. The odd closed question here and there would however not pose a problem, but when it becomes a trend during the questioning of the witness, a valid objection could be raised.

Examination in chief, as mode of questioning a witness, has the objective to extract from the witness information which is within the witness’ first-hand personal knowledge and is relevant to the matter in question.

Cross examination

In order to test the credibility and reliability of the witness, examination in chief is usually followed by cross examination by the opposing party.

Due to the fact that cross examination is aimed at identifying and exposing weak areas in the witness’ testimony, which the opposing party can capitalise on to its own benefit, it imposes a degree of functional restriction on the witness’ answers on the one hand, while allowing more freedom to the questioner regarding the framing of his/her questions, on the other.

As a matter of course, the questioner would depart from what the witness testified during examination in chief, singling out significant omissions, contradictions and statements regarded as improbabilities, “untruths” or blatant lies.

During cross examination, the examiner is allowed to resort to closed questions, restricting the witness’ answers to only a “yes” or a “no” reply to a question put to him/her. As much as the witness would want to put his/her answer within proper context, the cross examiner may not allow any such elaboration.

The cross examiner may also put speculative and unproven statements to the witness, just to test the witness’ consistency and resolve. Normally, such a statement will commence with the following introduction: “I put it to you that ….”.

When the cross examiner attacks a specific stance, argument or statement of the witness, exposing it as improbable, not credible or untruthful, it is advisable that, after discrediting the version of the witness in this way, the cross examiner fills the void, so created, with its own version, usually introduced with wording such as: “ … Is it not rather that what happened was …”.

On the other hand, it is advisable for the person calling the witness to anticipate, as far as possible, what the cross examiner may focus on during cross examination. Admittedly, it is not possible to prepare for every eventuality that may arise during cross examination, but one should at least expect that every bit of weakness known, will be capitalised on.

Anticipating the possible “damage” to be inflicted during cross examination, it would be strategically and tactically wise to canvass such weaknesses during examination in chief already, where the witness will be allowed to at least provide proper context to such apparent weakness, while, at the same time, disposing with the “surprise element” which the cross examiner would want to introduce.

Short of persistently and unnecessarily dwelling on a particular aspect, thus battering the witness, the cross examiner virtually has free reign when questioning a witness.

Re-examination

Due to the restrictions placed on the witness during cross examination, which, in some instances, may unfairly prevent the proper context of a particular relevant and important aspect being articulated, a re-examination opportunity is provided.

This implies that the person calling a witness is afforded a second opportunity to question his/her witness with the exclusive objective of doing “damage control” in respect of possible wrong perceptions created during cross examination. In essence, re-examination affords the witness the opportunity to elaborate on a relevant aspect canvassed during cross examination and when he/she was not given the chance to provide proper context.

Let me illustrate the application of re-examination with this elementary example:

An employee is subjected to a disciplinary hearing and is charged with failure to advise line management of his inability to report for duty, as required in terms of company policy. During examination in chief the employee testified inter alia that, on the morning in question, when he woke up, he was not feeling well and decided to rather stay at home, self-medicate and if his condition does not improve, to consult a doctor. That happened on a Friday and, fortunately, he recovered over the weekend and reported for duty on the following Monday (being a 5-day worker).

During cross examination he was asked whether he has a telephone in his house (that was before the advent of cell phones). In answering this question, he wanted to explain that, while there is a telephone in his house, the telephone was however not operative and that his parents reported the faulty telephone and was waiting for it to be repaired. He was also alone in the house on the Friday, as both his parents were at work. The cross examiner however did not allow him the opportunity to give this context and explanation, as he was pressurised to only answer “yes” or “no” to the question posed. He then answered “yes”, as it was true that he had a telephone in the house (albeit a defective one).

The cross examiner then put it to the employee that he was irresponsible, did not care about his job and disregarded the requirement to at least inform his employer when he is unable to report for duty, so that contingency arrangements could be made in the interim. Although the employee started responding to this statement by saying: “It was not like that…” he was cut short by the cross examiner who indicated to the decision maker that he had no further questions for the witness, thereby allowing the notion of carelessness and irresponsibility on the part of the employee to prevail in the mind of the decision maker.

Luckily for the employee, the person who called him as a witness, could resort to re-examination allowing the witness to place his failure to inform his employer via telephone of his inability to report for duty, within proper context. Effective “damage control” could therefore be exercised by means of re-examination.

Just bear in mind that only aspects that resulted from cross examination may be canvassed during re-examination. Re-examination may not be utilised in order to introduce additional evidence or to elaborate upon examination in chief.

Graphic illustration of the inter-relationship between the modes of questioning

The following picture (marked circle A) graphically depicts the impression or image created in the mind of the decision maker after having listened to the deployment of evidence during examination in chief. The lines within the circle representing the answers given during examination in chief.

The picture below (marked circle B) graphically depicts the impression created by cross examination in the mind of the decision maker. The lines running in the opposite direction representing the reaction solicited from the witness during cross examination in furtherance of the cross-questioner’s case.

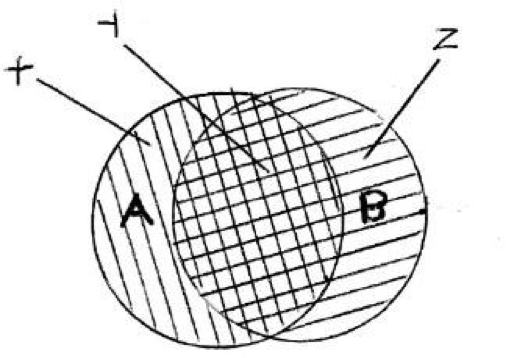

The picture below shows cross examination, depicted by the circle marked “B” overlapping with the circle marked “A”, which depicts examination in chief.

The section of circle “A”, not touched by circle “B”, indicated by “X”, represents “common cause factors” relevant to the case, implying that the information within this section emanated from examination in chief and remained unchallenged during cross examination. The decision maker can therefore safely regard this information as undisputed evidence.

The integrated section indicated as “Y”, which shows a checked pattern, represents information to the disposal of the decision maker, in respect of which the latter heard the opposing versions of the parties to the dispute being argued and substantiated as best they could and the decision maker will now have to decide which of the two opposing versions is the most probable.

The section of circle “B”, not touched by circle “A”, indicated by “Z”, represents information emanating from cross examination, not addressed during examination in chief and not put within proper context by way of re-examination by the employee party.

To the extent that this information is regarded by the decision maker as relevant to the case, but left unchallenged or not successfully challenged, also not corrected by the employee party, the decision maker may regard this information as “common cause” factors, as well.

In summary, dependent on relevancy to the case at hand, the information in the sections indicated as “X” and “Z”, is information the decision maker may take judicial notice of, thus regarding it as facts, fit to be introduced as evidence.

This leaves only the information in the section indicated as “Y”, in respect of which the decision maker has to apply his/her mind and determine the most probable of the opposing versions. Having done that, the decision maker can now complete the “puzzle” of the truth and formulate his/her reasoned findings.

A bit of a “What if”-scenario discussion related to testimony and questioning

No representative

Where the employee testifies out of own accord and is not called as a witness by a representative, the question arises: How will the facility of re-examination be utilised to the employee’s benefit?

It will be incumbent on the decision maker, acting in accordance with his/her inquisitorial role, to afford the employee such opportunity, possibly also explaining to the employee the purpose of re-examination, obviously in a neutral manner, so as not to be accused of taking sides or compromising his/her unbiasedness.

Credibility versus reliability

The credibility of a witness speaks to the truthfulness and sincerity of the witness, while the reliability of a witness has to do with the witness’ ability to provide truthful and factual information pertaining to the subject matter of the hearing.

Where a witness testifies about something he/she saw pertaining to the matter at hand, but, for instance, his/her eyesight may have been compromised due to not having worn his/her glasses at the time, or misty weather or darkness obstructed proper vision, the witness may be credible, as he/she truly testified about what he/she observed, but the witness is unreliable as result of impaired eyesight or poor visibility.

From this follows that a witness regarded as not credible is also unreliable, ipso facto (due to the fact of being not credible) as a witness , while the credibility of a witness, who is regarded as unreliable, due to circumstances as described in the former paragraph, will not be compromised.

Initiator/ “prosecutor” as witness

The initiator of the disciplinary case, being the representative of line management and owner of the charge, invariably also acted as the person who investigated the matter and therefore could have first-hand knowledge of certain relevant information pertaining to the case.

This implies that the initiator may fulfil a dual role in the proceedings. On the one hand officiating as management representative, presenting line management’s case by way of, inter alia, the calling of witnesses, while on the other hand officiating as a witness regarding those aspects of the case he/she has first-hand knowledge of.

Procedurally, it would be prudent for the initiator to officiate firstly as a witness, give testimony in examination in chief, avail himself/herself to be cross examined and being afforded the re-examination opportunity, if necessary. Once this is done, the initiator will then assume the role of management representative and call witnesses and present argument in support of line management’s case.

The accused employee is not called as a witness or elect not to testify in his/her defence

As indicated above, providing testimony is an enabler in respect of the employee who is charged with misconduct. While highly advisable, it is not mandatory to testify in one’s own defense in disciplinary proceedings.

Bearing in mind that, procedurally, line management will first present the case against the employee, substantiating the charge at least on a balance of probability, the opportunity given to the employee to testify in his/her own defense follows thereafter.

If the employee therefore is not called as a witness or elects not to testify in his/her own defense, he/she does so at his/her own peril, because he/she will leave the case brought against him/her unchallenged, thus unintentionally, but tacitly, giving credence to the case against him/her. The inference reasonably drawn from the employee’s failure to challenge the case brought against him/her, is likely to be that he/she is unable to refute the allegations against him/her.

With discharging the onus of proof of a balance of probability, the decision maker, in this instance, is likely to conclude that the employee is guilty as charged.

Electing not to cross examine

Where a party to a disciplinary hearing elects not to cross examine a witness after the latter testified in examination in chief, he or she is free to do so. It will however have the effect that he/she will tacitly give credence to the testimony of the witness by leaving it unchallenged. Similarly, credence will be given to any aspect of the testimony during examination in chief, not challenged during cross examination.

Electing not to utilise re-examination

The party to disciplinary proceedings who elects not to utilise the opportunity to reexamine its witness will lose the benefit of doing “damage control” in respect of any “damage” done to its case during cross examination. By the same token, the unrepresented employee who does not resort to re-examination in order to provide proper perspective and context to aspects canvassed during cross examination, will forfeit such opportunity.

There may however be a plausible reason for electing not to utilise re-examination, such as that, in the party’s considered opinion, the cross examination inflicted no damage to the case.

The witness turning hostile

Occasionally, it may happen that a particular witness, after being carefully prepared by the person calling him/her as a witness, while giving testimony, for some or other reason, deviates from the rehearsed testimony, to such an extent that he/she testifies against the case he/she was called in defence of.

In the article titled Disciplinary charge formulation, I alluded to this eventuality, in passing, recommending that the person preparing any witness should request the witness to state in writing what he/she knows about the matter at hand and sign and date such statement.

When it then so happens that a witness changed his/her testimony and testifies contrary to what he/she was prepared to testify, the person calling this witness can produce the signed statement made by the witness, in substantiation of the notion that the witness turned hostile.

Normally, one is not allowed to (and obviously would have no reason to) cross examine one’s own witness, but once the decision maker is duly convinced that the witness turned hostile, the person who called the witness is allowed to cross examine such witness.

A sworn statement from someone, containing seemingly relevant information, ispresented as evidence, as an alternative to the deponent testifying as a witness

The admissibility of the sworn statement as evidence in a hearing, where the deponent is not available as a witness, depends on the following:

- Whether the opposing party allows its submission as evidence after having acquainted himself/herself of its contents; or

- Whether there is other tested evidence available corroborating the contents of the affidavit.

In the absence of an affirmative response in respect of either of the two eventualities mentioned above, a sworn statement (or even a mere confirmatory statement) without the deponent testifying and being able to be cross examined, will be inadmissible evidence.

General notes

While the focus in this article is on internal disciplinary proceedings, the way the testimony of witnesses is to be treated, equally applies to any hearing, whether in internal disciplinary proceedings, CCMA / Bargaining Council arbitrations or labour court proceedings.

Where I used the terms “applicant” and “respondent” within this article, I did so for purposes of differentiation only, while admitting that these terms are generally used within context of CCMA proceedings and are not, as a rule, used within context of internal disciplinary proceedings.

Conclusion

As indicated above, the testimony of witnesses is one way in which evidence is deployed during hearing proceedings. As such, it plays an important role in placing relevant evidence before the decision maker, which will form part of the body of evidence on account of which he/she will ultimately base his/her decision on.

Because the human element is strongly associated with the testimony of witnesses, special caution should be taken in order to distil the trustworthy essence from each witness’ testimony, hence the different modes of questioning and associated principles contained in this article, being applicable.